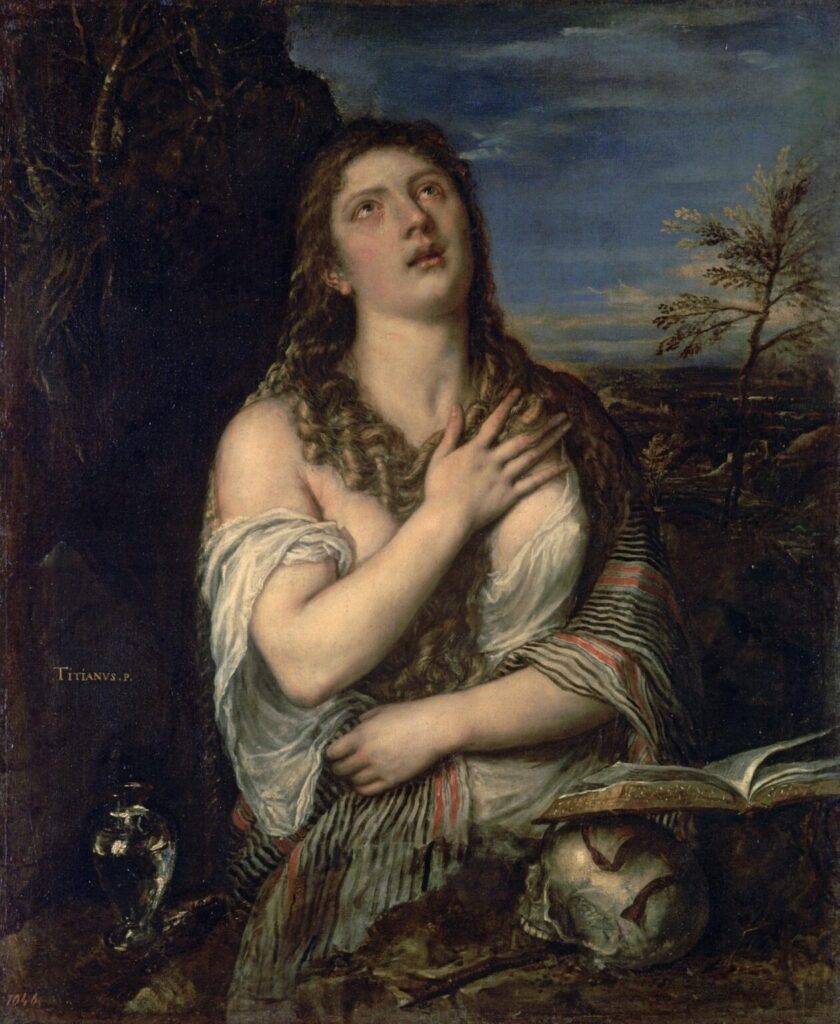

The smooth and pale skin of Mary in Titian’s Repentant Mary Magdalene (Fig.1) is partly covered with coarse clothes, and her transparent tears run off her face, which is raised to the sky in prayer. In the background, there are dark, rough rocks and an infinitely dramatic landscape. One step closer and the experience of this painting changes: the central elements of the composition convey even more detailed features and textures, whereas the rest of the canvas exposes the medium of painting and makes visible the physical engagement of the artist. Art History offers an extensive scholarship on Titian’s painting technique. His contemporaries discussed his works and defined his artistic. For example, Giorgio Vasari, writer of The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, 1568) coins Titian as one of the greatest artists of his time, comparing Titian with Michelangelo. In the 16th-18th century, the Venetian school and Titian’s technique: the virtuosity of his brushstrokes, the colour and compositional choices, influenced the development of British painting. The first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, Joshua Reynolds visited Venice in the 1750s and his study of the masterpieces noted the sublimity and the dramatic qualities of Titian’s paintings.[1] The British painter and printmaker William Blake (1757- 1827) also wrote: “Broken Colours & Broken Lines & Broken masses are Equally Subversive of the Sublime.”[2] Blake found that despite the greatness of Titian’s colours, the painting technique is lacking some attention to the drawing.[3]

URL: https://www.hermitagemuseum.org

In this essay, I will take a step beyond the chronological boundaries of Art History and discuss Titian’s Repentant Mary Magdalene from the perspective of Digital Media. In doing so, I aim to provide new interpretations of Titian’s practice and demonstrate its relevance today in the age of abundant digital technologies. I will approach painting as a source of information and consider the differences between fine and rough brushstrokes, examining Titian’s use of painterly technique and the experience he seeks to transmit to the viewer through such techniques. To bridge the chronological gap between today and the Early Modern period, I will study and draw parallels with ‘Three walking ladies‘.[6] Fig.2 by contemporary artist Vladimir Potapov (1980) and Titian’s Repentant Mary Magdalene. The main focus of this comparison is to trace the artistic strategy of representing reality whilst simultaneously manifesting the material qualities of painting. The first chapter is devoted to a theoretical overview of the concept of glitch and how the application of the term has shifted from the technological realm to different media within the field of visual art. By establishing an overview of the existing discourse, I will discuss the exchange of the term and its operation outside of the technological context. Each aforementioned painting will be described with a focus on its respective material and pictorial qualities. These descriptions will also touch upon the historical and cultural contexts in which the works were created.

Metaphorical meaning of glitch

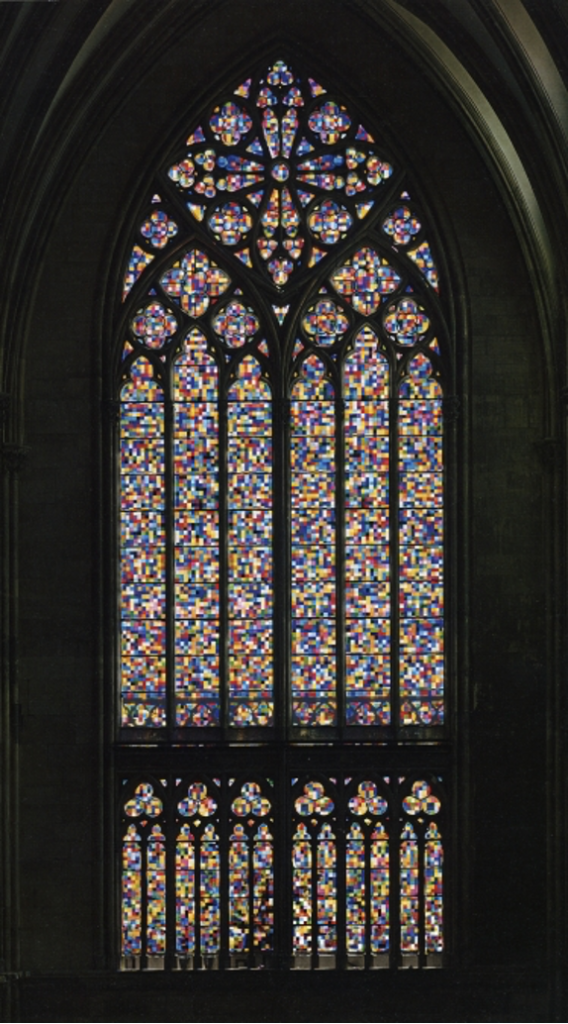

During the 1940s-1950s, the term glitch was commonly used as a slang word, used by radio and TV broadcasting companies in the United States. It referred to a mispronounced word or a technical interruption, perceivable by audiences.[7] In 1962, John Glenn, the first American astronaut, described the term in his essay, Into Orbit, as a simultaneous malfunction caused by a change of voltage in an electrical system.[8] Today, Glenn’s description frequently appears in academic writings in interlinked fields, such as Media and Cultural Studies, Social Theory, Art theory and Aesthetics; however, its definition has become broader. In this chapter, I will trace the expansion of the term from its initial meaning to a more metaphorical one and will discuss its characteristics beyond the technical context. Alexander Galloway was one of the first scholars to reflect upon the creative applications of technical errors. In his PhD dissertation, “Protocol, or, how control exists after decentralization” (2001), Galloway describes glitch as existing beyond the normal functionality of data flow.[9] Galloway regards the artistic outcome of such practice as having marginalized features: it goes against the mainstream culture by employing alternative methods of engaging with technologies; due to this, it carries its own specific aesthetic language, which involves corrupted data.[10] Furthermore, scholars, such Michael Betancourt, Mark Nunas, Olga Goriunova, Elvira Zhagun, among others, discuss the ideological dimension of glitch, regarding such artistic interactions with errors as being a reflection upon social and cultural structures in network societies.[11] Zhagun clarifies that in our age of digital technologies, defined by increased performability, standardisation, medium transparency and high resolution of photo- and video imagery, there is less room left for variability. Artists, therefore, engage with errors in order to put forward critical reflections on how precise algorithms regulate society. Moreover, through manipulating codes, artists find new meanings for images discarded by standardized systems. Such images, despite their corruption, contain recognizable fragments of reality and make the medium visible to a viewer.[12] In this regard, a metaphorical glitch in visual art can be defined as a perceivable loss of information, which offers a new aesthetic language, which typically incorporates and often juxtaposes the reality represented with its carrier. Furthermore, artists who engage with glitches strive to escape the banality of mainstream cultural structures, to break the established logic and to reflect upon the status quo. It is noteworthy that since the 1970s technical malfunctions and errors have been an important part of the experimental practice of visual and sonic artists. Paul Panhuysen, Kim Cascone, and Christian Marclay, among others, were engaged with technologies in an alternative way; for example, reconsidering the functionality of devices and exploring new aesthetic opportunities. Later, with the development of digital culture, glitch exited the technical realm and became common in mass culture, appearing in domestic design and visual art.[13] One example is that of the Italian designer Ferruccio Laviani (1960), who is known for his finely crafted glitch furniture made of massive wood. Fig. 3. Gerhard Richter (1932) created pixelated stained glass windows for the south transept of the Cologne Cathedral. Fig. 4 Wim Delvoye (1965) translated software processed images of real objects into sculptures made of cast iron. Fig.5 Although these examples have a visible connection to digital technologies, considering glitch in its metaphorical meaning can also be traced in traditional media, such as painting. In the next chapter, I will take a close look at the painting ‘Three walking ladies’ by the contemporary artist Vladimir Potapov and discuss what place metaphorical glitch takes in his artistic strategy.

Fig. 5. Wim Delvoye, Le Secret ( clockwise), 2011, Polished bronze ( unvarnished), 50x50x116 cm. Image source: https://wimdelvoye.be/

Potapov’s ‘Three walking ladies’

Vladimir Potapov was born in 1980 in Volgograd, Russia, and is currently based in Moscow. In an interview, he mentions that he did not follow the traditional path towards becoming a painter, whereby the prospective artist gains realistic painting and drawing skills during five years of formal study. After spending a year at the Volgograd State Institute of Arts, he took private classes from a local, self-taught artist, Boris Mackhov (1937-2014), who had exceptional painting skills. Potapov continued his education at the Institute of Contemporary Art and Culture in Moscow and the Open School MediaArtLab. Although these two institutions are not formal art education institutions, they nevertheless facilitated Potapov’s entrance into the contemporary art scene in Moscow. Potapov is a frequent participant of national and international contemporary art exhibitions, including Russian Art Week and the Curitiba International Biennale of Contemporary Art (Brazil); furthermore, his are in the collections of Moscow Museum of Modern Art (Russia), Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow, Russia), amongst others. Apart from his extensive artistic practice, Potapov is also known for his research project Ne vos’mis (Don’t even try), in which the artist interviews key figures in Russia’s contemporary art scene, in an effort to locate the essence of painting. In this chapter, I will examine one of his works, Three walking ladies (2015) and will, by considering the aforementioned definition of metaphoric glitch, contextualize his artistic strategy.

Three walking ladies (2015) depicts three young female figures in an urban environment. They are positioned close to one another, and the positions of their heads and posture give the impression that they are having a conversation. Due to the specificity of the painterly technique it is difficult to perceive their facial features; however, the high contrast between the shadows and light that fall upon on their faces emphasises their emotive expressions, showing a moment of joy. The background of the painting is reminiscent of a typical (post-)Soviet city with low concrete-panel apartment buildings, known as khrushchyovka.

The composition of the painting, the posture of the figures, and the colour characteristics suggest photographic source material. The relation between the painting’s figurative elements are similar to those of a camera’s snapshot. British art theorethist E.A. Gombrich (1909 – 2001) describes such a quality as an arrested moment.[14] According to Gombrich, the technical capacity of the camera allows it to capture a moment that the human eye is not able to trace. Such a fragment of reality or an arrested moment allows one to depict more than what a human can perceive.[15] In Three walking ladies, that arrested moment is present in the frozen movements of the figures, which are captured in action.

In the production of a photograph, the processing of the image within the frame does not depend upon what a human considers important or what he is capable of seeing; it is rather based on the photo-chemical reaction and the camera optics that allow the passage of light. It appears that the colour characteristics of Three walking ladies, namely their intensity, tune and the relation between light and darkness, have a photographic origin. This can be detected by dark parts of the painting, which are not distinct from the depiction of shadows. For example, the ladies’ faces, their dresses, the ground on which they are walking, and the buildings in the background have the same colours and intensity, which is typical for photography. The same can be observed with the illuminated parts of the painting.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes (1915 -1980) states in his book Camera Lucida that the photograph is not separate from its referent and the depiction of an object is perceived equal to the object itself.[16] Roland Barthes continues: “Whatever it grants to vision, and whatever its manner, a photograph is always invisible: it is not it what we see.”[17] It appears that Potapov is aware of these properties and incorporates them into his practice. Although the photographic nature of Three walking ladies is recognizable, Vladimir Potapov strives to move away from a photorealistic representation of reality. He literally breaks the painting’s surface and makes the carrier and the medium visible. The artist explains that he chooses plywood, which is made of multiple layers, and applies 15-16 coatings of different colours of acrylic enamel. After the paint dries he utilizes a sharp chisel to cut, both purposefully and accidentally, through these layers in a way that the friable wooden texture with its splinters and chips become visible to the viewer. Such physical interaction and manipulation create some wounds that appear accidental.[18]

The previous chapter provided a definition of metaphorical glitch, in which the artist breaks the illusion of a perfect reality and emphasizes the material aspect of an artwork. Potapov’s strategy appears to be similar: he paints a photorealistic image, employing something which an eye preconditioned by mass culture would find realistic, yet simultaneously he destroys the carrier of the information, thereby rendering the materiality of the carrier especially visible. The recognizable fragments of reality in the painting, the scratches and the chips all become equally integral parts of the viewer’s experience.

Considering the reactive nature of metaphorical glitch, through which artists reflect upon established mainstream culture, it is important to understand the response of Potapov to the environment in which he operates. In his lecture Zhivopis’: revizija, novye osnovy (Painting, its revision and new basis) he states that, “today in the age of digital technologies, standardisation, industrial production and the increase of digitalization, craftsmanship of painting appears to have a particular meaning. The first factories were completely dependent upon manual labor, and it remained this way for more than 100 years. Nowadays, the industry aims at excluding humans from the process. Earlier the industrial production required extensive collective labor, while today it is all operated by machines. Total automatisation and computerisation exclude the involvement of hands. The same counts for visual art, which strives to follow the most efficient and optimized way of artistic expression. Painting does not comply with those tendencies as an outdated and to some extent complicated medium. Therefore, contemporary painters are rather outsiders, who deny more successful strategies. However, painting is one of the oldest and most innate ways of human creative expression and can be compared with singing or dancing, thus it will remain an integral part of human existence.”[19]

It appears that, for Potapov, to engage with paint and to work with such a conservative medium means to critically respond to the current state of affairs, namely the position of painting in contemporary art. He explores the aesthetic capacity of fractured images and makes materiality visible for the audiences. This analysis of Three walking ladies has shown that metaphorical glitch can be located outside of the technological realm. This raises the question to what extent the aforementioned characteristics of metaphorical glitch can be present in an artwork from different periods of history. In the next chapter, I will examine Repentant Mary Magdalene, the work by Titian, who was described by his contemporary Giorgio Vasari as one of “the most excellent painters” of his time.

Repentant Mary Magdalene and Titian’s artistic strategy

As was previously discussed, metaphorical glitch can exist beyond the technological realm. Taking into account that information loss can be a purposeful part of the aesthetic experience in figurative painting, this chapter will examine The Penitent Magdalene, a work by Titian, and the context in which Titan created his masterpieces.

Titian painted The Penitent Magdalene in the 1560s. The work was stored in his house in Venice until his death in 1576. In 1850 it was acquired by The State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia, as a part of the Cristoforo Barbarigo collection.[20] This artwork depicts a Biblical story, which was in high demand at that time, whereby the artist brings together two considerations of female beauty. Its attributes were supposed to be simultaneous chastity and sensuality.[21]

Upon close inspection, one can see that the face of Мagdalene and the uncovered features of her body, such as the neck, chest and her hands, are represented with such high precision and realism that when stood only a short distance from the painting’s surface one can still clearly perceive the texture of her skin and the clarity of her tears. Magdalene’s face and chest, covered by her arms, are central elements in the composition of the painting. Here, the brushwork is not traceable. Thus, the artist has rendered the medium transparent or invisible. In contrast, Magdalene’s face and her body, the painting’s most illuminated areas, are framed with rough brushstrokes. These brushstrokes represent various textures: glass, paper and some other materials, with each of them painted in a different way, thereby emphasizing their material characteristics. For example, upon close examination, Magdalene’s clothing in the lower part of the work appears to be light and soft; it is depicted with translucent paint and the texture of the canvas is visible. Also, the glass ewer is ‘sculpted’ with a thick layer of white pigment, which is sticking out from the surface of the painting and emphasises its hardness and its transparency. Titian achieves the work’s visual effect by contrasting his fine brushstrokes, where the medium is completely dissolved by the depicted bits of reality, with rough brushwork, in which we can trace each movement of his hand and the irregular texture of the canvas. He combines a highly detailed depiction with abstract gestures that carry reduced information. On the level of observation, this feature of the work, as well as the materiality visible to the audience, can be considered as one of the aforementioned characteristics of a metaphorical glitch. However, art history scholarship approaches Titian’s technique differently. The scholar Christopher J.Nygren mentions, in his article “Titian’s “Ecce Homo” on Slate: Stone, Oil, and the Transubstantiation of Painting”, with the references to extensive scholarship, the importance of the canvas’ materiality and the tactility of brushstrokes in the picture-making process in Titian’s practice after the 1540s. He states, that “…by the middle of the sixteenth century Titian had begun exploiting the striated surface of the roughly woven canvas to great pictorial effect; canvas veiled with scumbled paint produced a surface analogous to the flesh.”[22] Furthermore, Christopher J.Nygren sees differences in how Titian tackles different surfaces, such as canvas and stone, and how the artist adjusts his painterly technique, the quality of the brushstrokes and the way of handling pigment.[23] Such an artistic approach does not separate the represented matter from its carrier, despite the fact that the texture of the canvas is visible to the viewer. The same is noted by British scholar Tom Nichols: “The expressive life of the surface becomes part of the experience of the picture, the process by which the painting comes to carry meaning is partially revealed.”[24] In this regard, that realistic representation in Titian’s work is not limited to the fine brushstrokes and medium transparency but incorporates a variety of material textures.

In the contemporary example discussed in the previous chapter, the artist voluntarily destroys the photorealistic depiction of reality, whereas Titian explores the expressive and aesthetic potentials of the material, deviating from the imitation of nature. Tom Nichols sees in that deviation a response to the cultural and intellectual climate in which the artist created his masterpieces. Although Vasari regards Titian as the greatest Venitian artist, according to Nichols Titian was separated from the Venitian artistic circle. He did not receive the same recognition as his contemporary Michelangelo’s in Florence was. He did not have an extensive workshop with pupils to pass on his skills to the younger generation, and his artistic approach did not fit into the established local canons. Giovanni Bellini (1430-1513) and Giorgione (1470s-1510) contributed to the Venitian canon, and Titian, who at the beginning of his artistic career was highly influenced by these masters, later prioritized his independence and self-expression over the family operating workshops.[25]

Such an outsider’s position is similar to what Vladimir Potapov discussed about the status of painting in the contemporary art world. For an artist, to break with the established tradition is also an escape from its banality. Furthermore, it is a matter of audience expectations and what they anticipate of their experience of art, as well as how the artist acknowledges and responds to these expectations in his practice.

There is extensive documentation of the responses expressed by Titian’s contemporaries on his technique. For example, Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists reflects on the painting method in the period between 1550-1560 and implicitly describes the expectations of the audience: “. . . these last works are executed with bold, sweeping strokes, and in patches of colour, with the result that they cannot be viewed from nearby, but appear perfect at a distance.” Another of Titian’s contemporary, Antonio Perez, a Spanish statesman and secretary to King Philip II of Spain, wrote in his private correspondence as follows:

“One day the ambassador Francisco de Vargas asked [Titian] why he had turned to that style of painting… with broad brushstrokes, almost like careless splotches…. and not with the sweetness of the brushwork of the great painters of his time; Titian responded: ‘Sir, I wasn’t sure that I could succeed at the delicacy and beauty of the brushwork of Michelangelo, Raphael, Correggio and Parmigianino, and even if I were to succeed, I would be considered less than they, or considered their imitator.”[26]

It appears that Titian resisted the established and recognized method of artistic production, in which painting remained to be a transparent medium per the use of smooth brushstrokes. As Vasari, the ambassador Francisco de Vargas associated such smooth technique with extensive efforts. Titian, however, demonstrates to them an alternative way of engaging with the medium and makes apparent that the result of such an approach also carries an expressive power. Furthermore, Titian’s artistic approach was a response to the established tradition of painting. He escapes the banality of the artistic expression and explores the aesthetic potential of the medium by acknowledging its material properties. In this regard, Titian’s practice in large extent is similar to the practice of contemporary artists who embrace errors, malfunctions and unexpected breaks in the established logic.

Conclusion:

In this paper, I have provided analyses of two artworks that, despite having been produced in distinct time periods and socio-cultural contexts, bear an alikeness in terms of how the respective artists have approached the medium. Through these analyses, it has been possible to situate Titian’s Repentant Mary Magdalene in relation to contemporary Digital Media.

In the first chapter, I provided a review of the existing discourse surrounding the concept of glitch. I first contextualised the historical emergence of the term, and then addressed the application of the concept as an artistic strategy in the field of digital arts. Drawing on this foundation, I proposed an expanded application of this concept, namely the metaphoric glitch. The metaphoric glitch can be understood as a strategy that applies not only to how the artist approaches the materiality and aesthetic properties of his medium but equally to how he responds to the established traditions and expectations that pertain to that very medium and the art experience in general. The metaphoric glitch sees the medium subverted, as much materially as culturally, whereby the subversion is detectable in both the work’s narrative and material content.

In the second and third chapters, I reviewed Titian’s Repentant Mary Magdalene (1560s) and Potapov’s Three walking ladies (2015). These analyses entailed a description of the aesthetic and material qualities of the respective works, in addition to further contextualisation with secondary and primary sources. In the case of Potapov, only primary sources were used, namely interviews, due to a lack of secondary sources.

By drawing a comparison between the works of Titian and VladimirPotapov, whose works have been produced almost five hundred years apart, I have demonstrated that the defining properties of the metaphoric glitch can be traced in artistic traditions long before the advanced digital technologies. Glitch is therefore not an exclusively digital concept, and the painting of Titian can be potentially understood as a forerunner of artistic strategies that we today associate with Digital Media.

The practice of painting has been and yet remains a sustained discipline in the world of art, just as Vladimir Potapov elaborates in his research. Though we live in a digital age that necessarily has implications on contemporary artistic discourse, the discipline and materiality of painting yet still hold a place within such discourse, on account of how overlaps between digital and analogue strategies can be detected in painting practices.

Bibliography

[1] Mannings, David. “Reynolds in Venice.” The Burlington Magazine 148, no. 1244 (2006): 754-63., p. 757

[2], [3] Lee, Eric McCauley. “”Titanus Redivivus”: Titian in British Art Theory, Criticism, and Practice, 1768-1830.” Order No. 9731056, Yale University, 1997., p. 296-297

[4] Wood, Jeremy. Rubens: Copies and Adaptations from Renaissance and Later Artists: Italian Artists. II: Titian and North Italian Art. Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard; Pt. 26,2. London [etc.]: Harvey Miller, 2010., p. 25-27

[5] Nygren, Christopher J. “Titian’s Ecce Homo on Slate: Stone, Oil, and the Transubstantiation of Painting.” The Art Bulletin (New York, N.Y.) 99, no. 1 (2017): 36-66., p. 3

[6] Initially the work has no title, with the permission of the artists, in this paper I named it as ‘tree walking ladies’.

[7] Zimmer, Ben. “The Hidden History of “Glitch.”, URL:www.visualthesaurus.com

[8] Glenn, Carpenter, Dill, Glenn, John, Carpenter, Scott, and Dill, John. Into Orbit. London, 1962., p. 60

[9], [10] Galloway, Alexander, “Protocol, Or, How Control Exists after Decentralization”, PhD diss., Duke University, 2001.

[11] Nunes, Mark. Error: Glitch, Noise, and Jam in New Media Cultures. New York: Continuum, 2011., p. 4

[12] Elvira Zhagun, “Glitch art – Aesthetics of the Error” YouTube Video, 1:14:53, URL: https://youtu.be/5-5vNcIw1oU

[13] Moradi, Iman. “Glitch Aesthetics.” BA [Hons], diss., The University of Huddersfield, 2004., URL:http://oculasm.org/glitch

[14] Gombrich, E. H. . Standards of Truth: The Arrested Image and the Moving Eye. Critical Inquiry, 7(2), 1980, p.237

[15] Ibid., p. 238-239

[16], [17] Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida.New York: Hill and Wang, 1981., p. 5-6

[18] “Хроники изоляции. Мастерская Владимира Потапова. 5.04.2020” URL:https://youtu.be/rzHaRKd0b2I

[19] “Лекция “Живопись: ревизия, новые основы”, Владимир Потапов, ЦСИ “Типография” (Краснодар)” YouTube Video, 1:07:12, Accessed on 19.01.2022, URL: https://youtu.be/5RUjPbilTZ0

[20] The State Hermitage Museum, URL: https://www.hermitagemuseum.org/

[21] Phillips, Claude. The Later Works of Titian. 2007., URL: www.gutenberg.org/files/12657/12657-h/12657-h.htm

[22] Nygren, Christopher J. “Titian’s Ecce Homo on Slate: Stone, Oil, and the Transubstantiation of Painting.” The Art Bulletin (New York, N.Y.) 99, no. 1 (2017)., p. 19

[23] Nygren, Christopher J. “Titian’s Ecce Homo on Slate: Stone, Oil, and the Transubstantiation of Painting.” The Art Bulletin (New York, N.Y.) 99, no. 1 (2017)., p. 36

[24] Nichols, Tom. Titian and the End of the Venetian Renaissance. London: Reaktion Books, 2013., p. 9

[25] Ibid., p. 20, 25

[26] McKim- Smith G., Andersen-Bergdoll G. and Newman R., Examining Velázquez New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988., p. 24